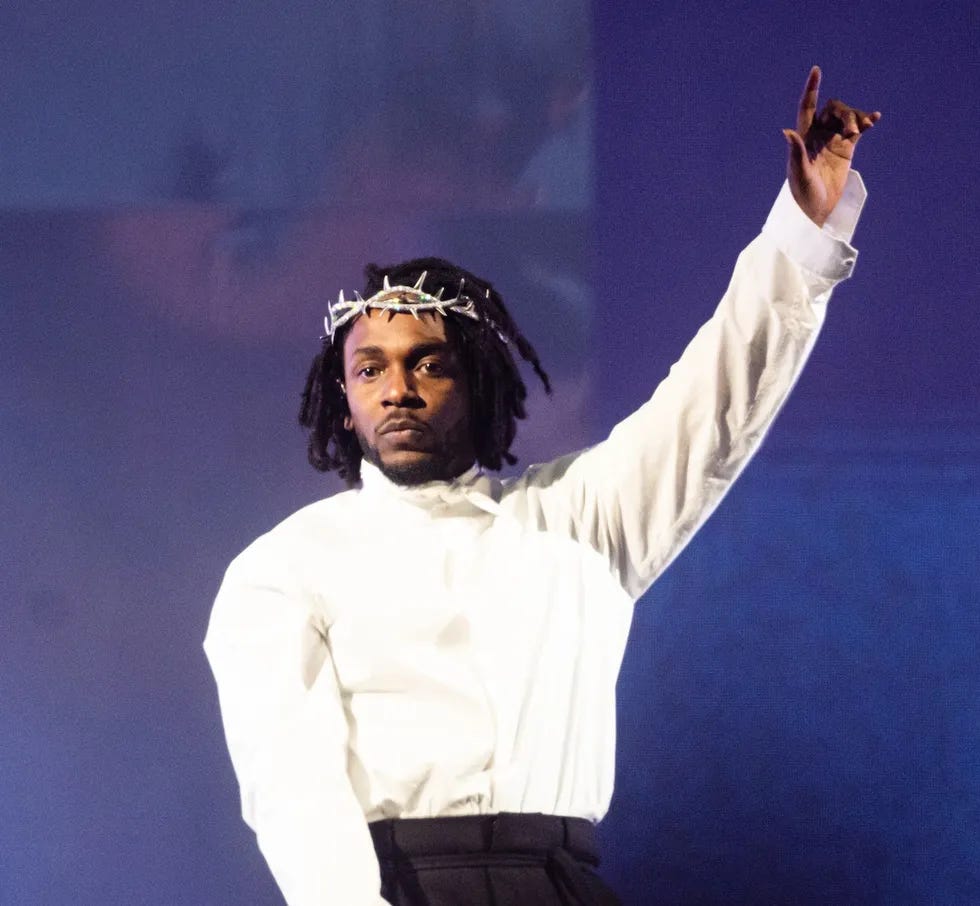

Kendrick, the Monarch

Kendrick Lamar finally delivered his response to Drake, and I don’t know whether to bop my head or throw my panties.

A six minute and twenty-four second diss track. EUPHORIA.

Indeed Kendrick Lamar, with his response to Drake at last, spiraled the culture into the most unexpected sonic levitation in recent memory.

Today felt like Black Christmas in April. We’ve all just had a hefty serving of Grandma’s classic dressing with cranberry sauce. Just as the sun is setting, we slip out the back door with our cousins for a walk to the neighborhood park to smoke the purest kush. And with near perfect timing, Unc pulls out the Henny spiked Lemonade from his left jacket pocket. Unc for the win. K.Dot for the win.

”Euphoria” opens over Teddy Pendergrass’s “You’re My First, My Greatest Inspiration.”

Teddy P., Kendrick? Teddy P?!

A surprising palate cleanser for the most decadent hip hop feast—something like The Last Supper. Because who calmly spits a massacre over an early eighties Quiet Storm jawn like he’s soaking in a bathtub doused with sunflowers? I mean, I don’t know whether to bop my head or throw my panties.

In “Euphoria”, there are nearly three different compositions in this one song, and three different vocal inflections. GODDAM.

And Kendrick went ahead and said it—said what is inarguably foundational to this generational hip hop melee, “We don’t wanna hear you say nigga no mooooo.”

“How many more Black features 'til you finally feel that you Black enough?

I like Drake with the melodies, I don't like Drake when he act tough.”

Kendrick Lamar’s “Euphoria”

Since his ascent to the rap scene in 2009, Drake has freely and near inconsequentially played tic-tac-toe with Black Diasporic identities. On one album he’s Caribbean and on another he’s a dirty South boi. As he made his way to global stardom, Drake’s Al Jolson minstrelsy reached new heights. The Toronto native’s once tender emo-laden R&B tracks like “Fancy”, “Shut it Down” to “Take Care”, and “Hotline Bling” soured to a misogynistic, gangsta rap “SNL” spoof. What was “Her Loss” in 2022 other than a poisonous soundbath for Kevin Samuel’s disciples?

Just when we all thought Aubrey was comfortable being Kanye West’s dilettante—suburban, talented and charmingly corny, he now gives the “Toxic King” Future himself a run for his Magic City cash stack. But Drake seems to have pissed off the generous donors to his street cred.

On March 22, when Future teamed with super producer Metro Boomin—two of Drake’s once frequent collaborators—to release “We Don’t Trust You”, followed by “We Still Don’t Trust You”, it was evident the donors failed to receive a return on investment. Or at minimum: loyalty.

A failure to be principled is precisely what got Drake in this industry warfare to begin with.

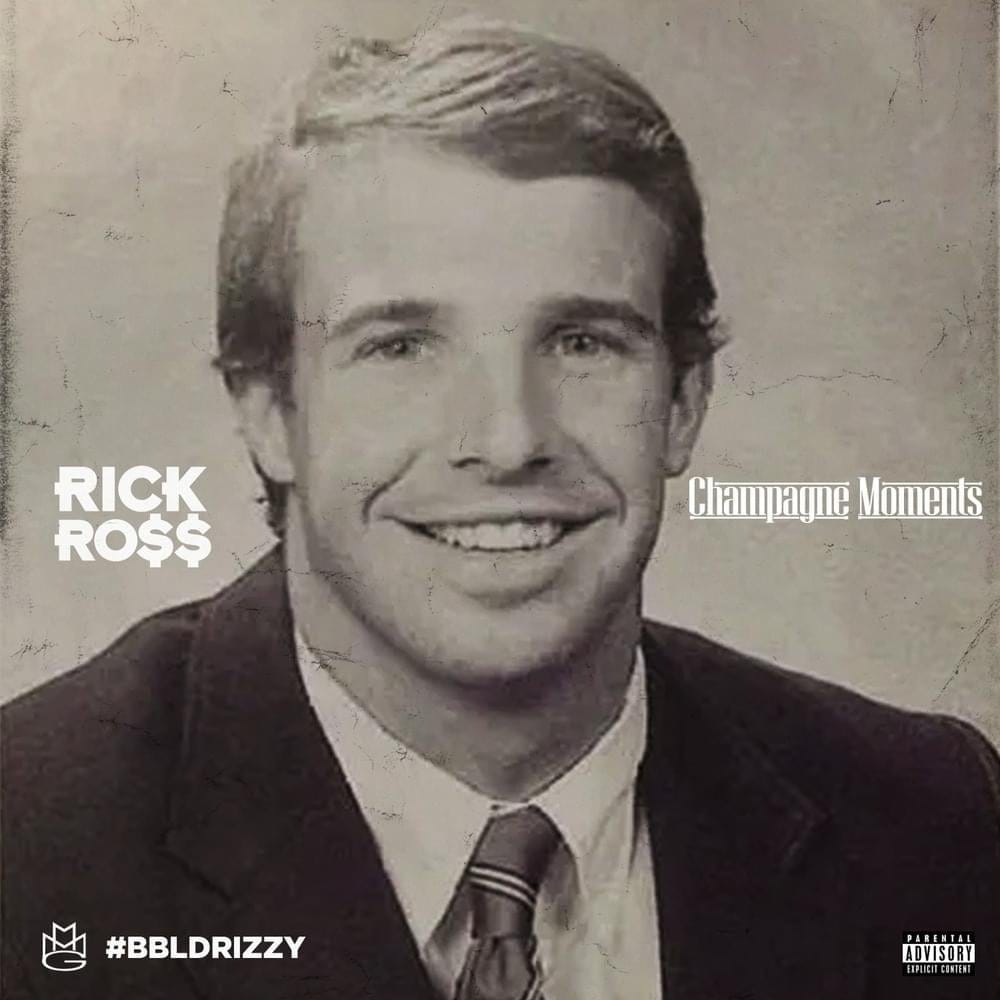

Although it hasn’t been clearly stated by Future or Metro, Drake committed to a follow up to the 2015 collaborative album “What a Time to be Alive”. Apparently Future and Metro put up a significant investment toward the project—Metro produced much of the album. Instead of following through, Drake paired up with his Canadian brethren 21 Savage to release “Her Loss” in 2022. Understandably, it enraged Future and Metro. If that isn’t enough, according to Ross, as he spits in “Champagne Moments”, Drake sent a cease and desist through his attorneys to French Montana preventing him from using a verse on the 2021 song “Splash Brothers.” “I unfollowed you, n***a, 'cause you sent the motherfuckin' cease-and-desist to French Montana, n***a,” Ross raps.

Using crafty legal maneuvers is evidently an ongoing tactic for the former child actor. It’s against the culture code, and certainly street code, to talk through attorneys, instead of working through frustrations directly, man-to-man. It’s also enormously dishonorable to stop fellow hip hop artists from releasing music, and thus, potentially preventing them from earning. Drake’s verse on French Montana’s monster hit “Pop That” propelled him to a new found status within culture, with street cred. The 2012 song also featured Ross, and Young Money boss Lil Wayne.

The message back door, hostile business tactics sends to these artists is now that Drake has reach international, record-breaking success—with the kind of cross-over appeal most non-palatable Black artists aren’t able to achieve due to racial bias and systemic racism—he doesn’t need them anymore. Drake’s half Jewish identity and years-long transactional and voyeuristic Black cultural cosplay is at the heart of these shots on wax, because the music industry even in 2024 remains largely owned and operated by white Jewish men. The optics suggest Drake weaponizes his proximity to whiteness when it benefits him, while simultaneously leveraging his procured street cred, these same artists so generously offered him in the early stages of his career.

According to Lamar on “Euphoria”, Drake also sent a cease and desist to prevent “Like That” from releasing. “Try cease and desist on the ‘Like That’ record. Oh, what? You ain't like that record. ‘Back to Back,’ I like that record. I'm gonna get back to that for the record.”

Comparable to his legendary “King of New York” diss on Big Sean’s 2013 track “Control (HOF)”, Kendrick took the first swing on the fast-paced track “Like That” aimed narrowly at the owl’s beak. It’s been a lyrical sparring war ever sense.

Kendrick joined with Future, Metro Boomin, and Rick Ross to take down Drake with coordinated missiles.

Ross went so far as to taunt Drake with a “white boy” disciplinary dress down at the close of his diss “Champagne Moments”. The cover art presents a black and white portrait of a Drake doppelgänger in a suit with a striking resemblance to the “Lady Sings the Blues” actor Paul Hampton. Hampton stars as Harry in the 1972 Billie Holiday biopic alongside Diana Ross. Harry is a songwriter and music industry veteran who becomes a shady operative in Holiday’s life and hooks her on heavy drugs during their tour of the American south in the thick of Jim Crow. Addiction and financial disenfranchisement claimed Holiday’s life when she died in 1959. The suit the Hampton look-a-like wears on Ross’s cover art is an allegorical representation of industry suits, who are predominantly white Jewish men.

It’s everybody vs. “Degrassi’s” own, and the sweeping response from Twitter (I refuse to call it X) to Tiktok is clear: the culture is wholly tired of Aubrey’s cosplay.

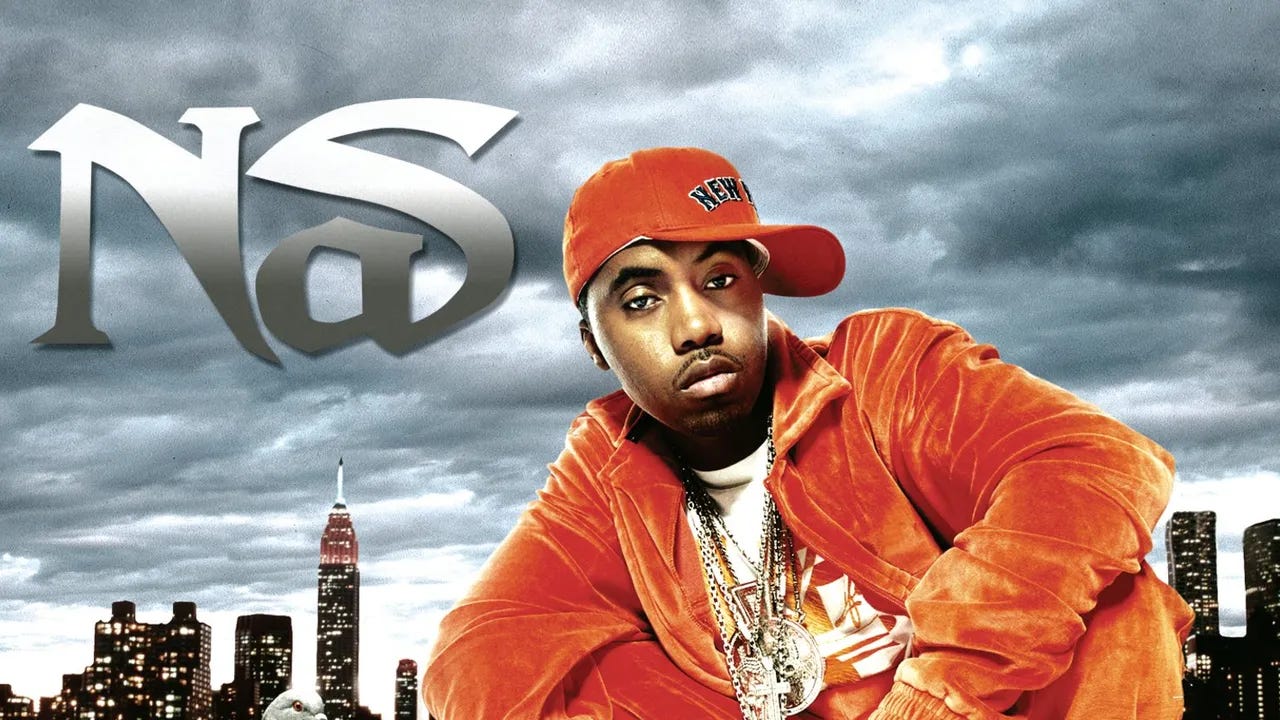

I mean, the density, the double entendres and lyrical cruelty for raw truth in Kendrick’s composition. “Euphoria” is the closet thing today’s hip hop will ever get to Nas’s “Ether.” Jay Z offered up “Supa Ugly” in response to “Ether” but it was an anti-climatic jab back at Queenbridge’s own, and even Jay knew it.

But in 2001, four years after the back-to-back murders of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.IG., what made the return of hip hop’s non-violent beef so exciting for the culture is that it was truly a rare match of lyrical peers. Hip Hop’s Michael Jackson vs. Prince.

Over 20 years later, one of music’s most commercially dominate star’s attempt at a public joust with Mr. Duckworth was a notoriously bad idea. Drake is simply out of his range. He’s missing the anointing, the sanctification, the grit. Even my feelings are hurt for Drake.

“Euphoria” signals a Shakespearean-level murder scene in the town square. The most thieving thief in the night on a Tuesday afternoon kind of slaughter. An end of an era and the opening of a door Elegua meets Shango style.

This moment in hip hop will be studied, and dissected from street corners to academia.

Decades from now, observers will agree: this was day when hip hop’s most formidable maverick ended hip hop's most relentless magician.